Chaining commands (Part 2: Redirections and pipes)

Redirections are a major feature of Bash, and yet, there are usually largely misunderstood. In the following, I will use schemes to illustrate redirections.

Disclaimer: even though redirections are intrinsically pointers (i.e. adresses) and therefore should be rigorously described and manipulated as such, I find it painful for daily use (and seeing the confusions that exist on this subject, I am clearly not alone). Consequently, I propose here another representation of redirections (treating them as content, rather than pointers) than I find much more practical for everyday use. One consequence being that redirections should (much more naturally, in my opinion) be read from right to left. I know it might sound like heresy to Bash experts, but I believe it is much easier to use that way.

Autopsy of a command

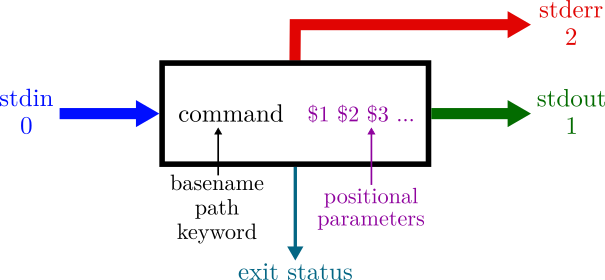

Let us start with some vocabulary:

One could also mention the PID and signals, but these will not be discussed here.

stdin (standard input), stdout (standard output) and stderr (standard error) are a special kind of files, called file descriptors. Each process can create and use up to 9 file descriptors (this mechanism will not be discussed here), but those three are always present by default (they can be seen by typing ls /proc/self/fd).

There is usually some confusion between the standard input and the arguments. Those are two completely different concepts (Even if most commands read from standard input if no input file name/path were given as arguments (or if - were given), to further add some confusion...).

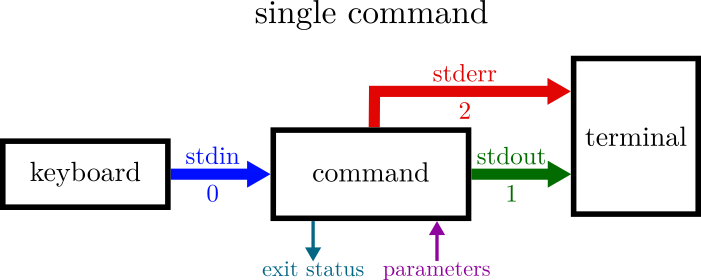

Bash redirections simply mean redirecting those file descriptors. So, let us start with the default case: where are redirected those file descriptors when you execute a "naked" single command in your terminal? The answer is just below:

As you can see, by default, stdout and stderr are both redirected to the corresponding controlling terminal (located at /dev/tty). In fact, stdin reads also from /dev/tty (yes, it is a very special kind of file, called device file), but that can be confusing, so I prefer simplify it.

This behavior makes it hard to distinguish those output of your command, and is the reason why your find commands results are usually spammed by error messages. But believe me, the distinction is quite real!

Example: ls /tmp/ /oops/ prints both the errors and the results.

Simple redirections

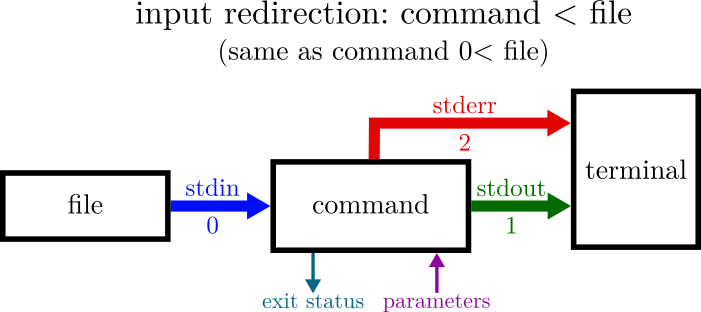

One can ask a command to read from a file instead of the keyboard (some rare programs require it):

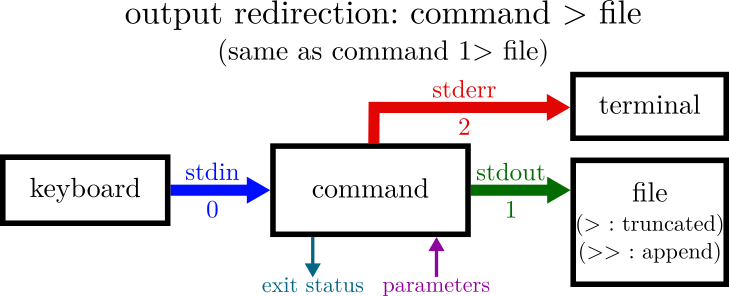

Or redirect the standard output of a command (as in cp2k.sopt -i MD.in > MD.out):

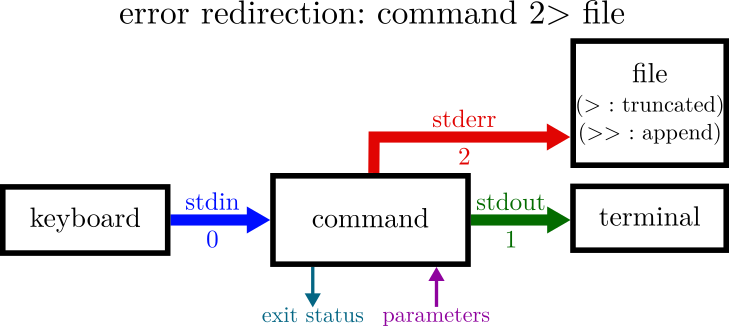

Or finally the standard error of a command (to keep a log file: ./configure 2>> install.log, or simply banish all errors to the void: find ~login -name "*.j" 2> /dev/null):

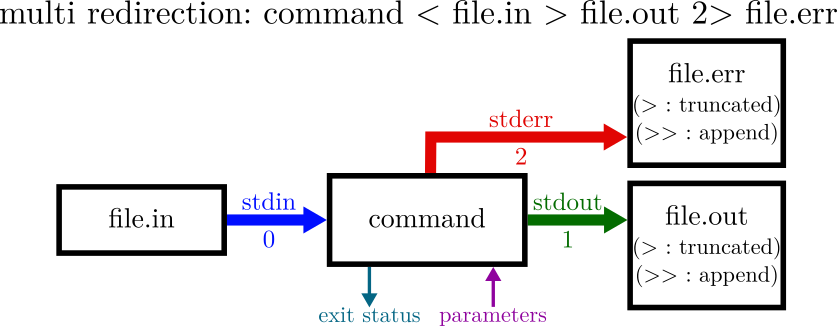

Now, all together:

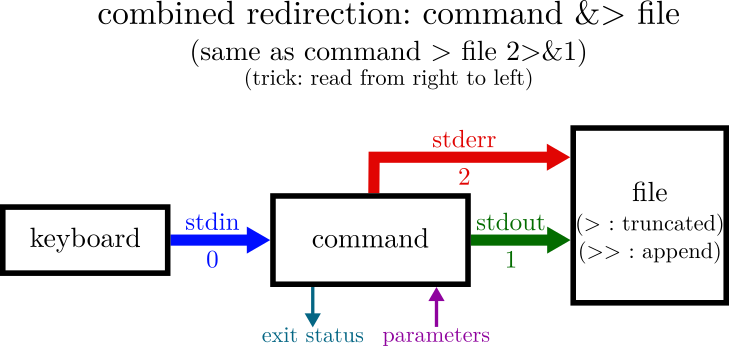

What if I simply want to write both standard output and standard error to the same file? In that case, you don't need to type > /path/to/file 2> /path/to/file (which is painful). You can use a combined redirection:

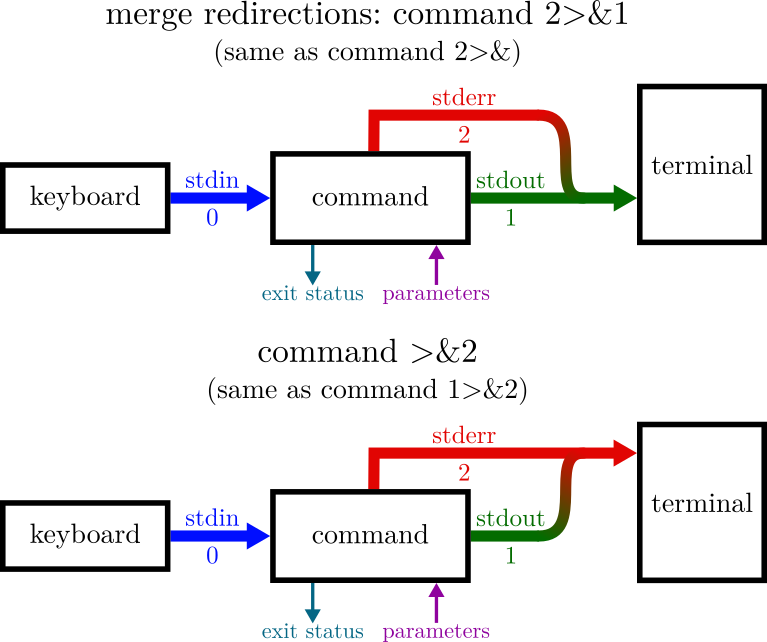

Merging file descriptors

A file descriptor can also be merged to another:

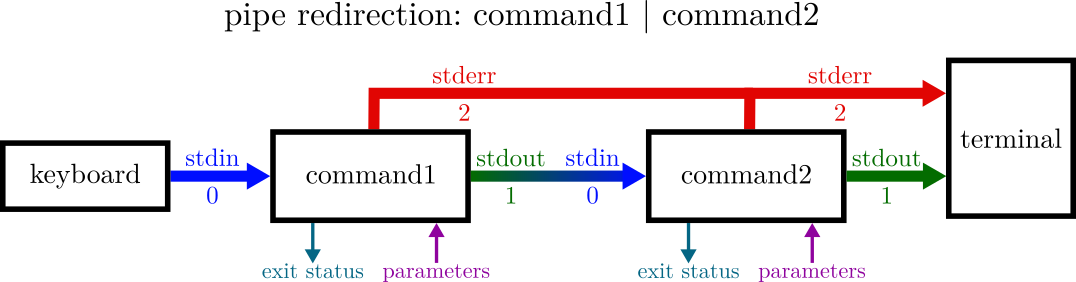

Pipes

Pipes are a very smart way of chaining commands without the need to buffer temporary results. And were developped when memory was expensive. Nowadays, memory is much cheaper, but this mecanism is still useful in many cases (in particular, for quickly processing a large file).

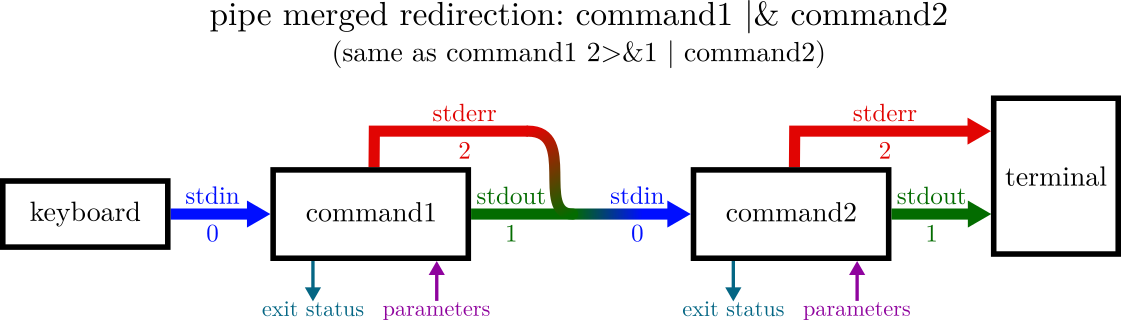

The redirection behind is simple but powerful:

As you can see, the standard input of the previous command is redirected to the standard input of the next command. So that each command reads its stdin from the stdout of the previous command.

Beware: a pipe can really be seen as flow of information that is processed "as it comes". Therefore, the execution order of the specified commands is not guaranteed!

Example: for i in {1..1000};do printf 3 >&2 | printf 4 ;printf '\n';done |& sort | uniq -c

In this last example, I made use of merging and piping together with a special syntax described here: